In seven years of offering investment management services to captive insurance companies, we are acutely aware how conservative many captive owners are when it comes to investment objectives and goals. A cookie cutter “one size fits all” approach does not work when it comes to constructing investment portfolios. The makeup of a captive insurance company’s portfolio should take into account the type of risk insured, projected loss patterns, and cash needs. In some cases, captive owners are so risk averse that they choose not to invest and are content to sleep well at night by owning money market funds and cash. Among captive managers, accountants, and actuaries, quite a few people have asked me, “What is the cost of NOT investing?”

Even in today’s low interest rate environment, the opportunity cost of not investing can be significant. The key is the concept of compound interest. This what Wikipedia says about the subject:

Compound interest arises when interest is added to the principal of a deposit or loan, so that, from that moment on, the interest that has been added also earns interest. This addition of interest to the principal is called compounding. A bank account, for example, may have its interest compounded every year: in this case, an account with $1000 initial principal and 20% interest per year would have a balance of $1200 at the end of the first year, $1440 at the end of the second year, and so on.

Let's look at an example.

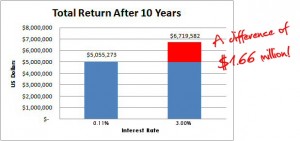

Suppose a captive has investable assets of $5,000,000. According to the Informa Research Deposit Report as of 8/21/13, the average money market fund had an Annual Percentage Yield of 0.11%. Compounding at this rate for 10 years results in $5,055,273.

Alternatively, let's assume that the captive invested in US Treasuries, and a very small portion to stocks, which very conservatively returned an average 3.0% annually. After 10 years, the portfolio would be valued at $6,719,582. The power of compounding is powerful, and the cost of not investing in the case is $1.66 million!

This is a very simplistic illustration, of course, since we are assuming that the annual rate of return remains low and does not change over 10 years. I will save discussion of specific investment strategies for captive insurance companies for another article. Notably, no contributions to capital and surplus were included here so the actual capital appreciation may be understated. The conclusion is that the cost of not investing one's captive assets can be meaningful; and like with retirement planning, the earlier one starts – the better.

In seven years of offering investment management services to captive insurance companies, we are acutely aware how conservative many captive owners are when it comes to investment objectives and goals. A cookie cutter “one size fits all” approach does not work when it comes to constructing investment portfolios. The makeup of a captive insurance company’s portfolio should take into account the type of risk insured, projected loss patterns, and cash needs. In some cases, captive owners are so risk averse that they choose not to invest and are content to sleep well at night by owning money market funds and cash. Among captive managers, accountants, and actuaries, quite a few people have asked me, “What is the cost of NOT investing?”

Even in today’s low interest rate environment, the opportunity cost of not investing can be significant. The key is the concept of compound interest. This what Wikipedia says about the subject:

Compound interest arises when interest is added to the principal of a deposit or loan, so that, from that moment on, the interest that has been added also earns interest. This addition of interest to the principal is called compounding. A bank account, for example, may have its interest compounded every year: in this case, an account with $1000 initial principal and 20% interest per year would have a balance of $1200 at the end of the first year, $1440 at the end of the second year, and so on.

Let's look at an example.

Suppose a captive has investable assets of $5,000,000. According to the Informa Research Deposit Report as of 8/21/13, the average money market fund had an Annual Percentage Yield of 0.11%. Compounding at this rate for 10 years results in $5,055,273.

Alternatively, let's assume that the captive invested in US Treasuries, and a very small portion to stocks, which very conservatively returned an average 3.0% annually. After 10 years, the portfolio would be valued at $6,719,582. The power of compounding is powerful, and the cost of not investing in the case is $1.66 million!

This is a very simplistic illustration, of course, since we are assuming that the annual rate of return remains low and does not change over 10 years. I will save discussion of specific investment strategies for captive insurance companies for another article. Notably, no contributions to capital and surplus were included here so the actual capital appreciation may be understated. The conclusion is that the cost of not investing one's captive assets can be meaningful; and like with retirement planning, the earlier one starts – the better.

By

In seven years of offering investment management services to captive insurance companies, we are acutely aware how conservative many captive owners are when it comes to investment objectives and goals. A cookie cutter “”one size fits all”” approach does not work when it comes to constructing investment portfolios. The makeup of a captive insurance company’s portfolio should take into account the type of risk insured, projected loss patterns, and cash needs. In some cases, captive owners are so risk averse that they choose not to invest and are content to sleep well at night by owning money market funds and cash. Among captive managers, accountants, and actuaries, quite a few people have asked me, “”What is the cost of NOT investing?””

Even in today’s low interest rate environment, the opportunity cost of not investing can be significant. The key is the concept of compound interest. This what Wikipedia says about the subject:

Compound interest arises when interest is added to the principal of a deposit or loan, so that, from that moment on, the interest that has been added also earns interest. This addition of interest to the principal is called compounding. A bank account, for example, may have its interest compounded every year: in this case, an account with $1000 initial principal and 20% interest per year would have a balance of $1200 at the end of the first year, $1440 at the end of the second year, and so on.

Let's look at an example.

Suppose a captive has investable assets of $5,000,000. According to the Informa Research Deposit Report as of 8/21/13, the average money market fund had an Annual Percentage Yield of 0.11%. Compounding at this rate for 10 years results in $5,055,273.

Alternatively, let's assume that the captive invested in US Treasuries, and a very small portion to stocks, which very conservatively returned an average 3.0% annually. After 10 years, the portfolio would be valued at $6,719,582. The power of compounding is powerful, and the cost of not investing in the case is $1.66 million!

This is a very simplistic illustration, of course, since we are assuming that the annual rate of return remains low and does not change over 10 years. I will save discussion of specific investment strategies for captive insurance companies for another article. Notably, no contributions to capital and surplus were included here so the actual capital appreciation may be understated. The conclusion is that the cost of not investing one's captive assets can be meaningful; and like with retirement planning, the earlier one starts – the better.